I am writing this in bed with a cozy blanket and a dog at my feet. Rain is just starting and I can hear it rustling the leaves outside my window. I am awake (again) so early in the morning because I am filled with excited anticipation. In just a few hours, fifteen kids will enter my classroom for the first time. I spent hours yesterday unloading, unpacking and moving back in all the comfy chairs, pillows, beanbags and loveseat, bringing my classroom back to its pre-pandemic set-up. The process brought me unspeakable joy. Gone are the rows of desks, set six feet apart, where my kids sat all day every day this past year. Gone is the teacher’s chair where I spent more time than I ever have, strapped to a specific spot in the room in order to present where all could see. Gone are the individual sets of supplies and materials. I welcomed back all the choice, flexibility and comfort that makes my classroom a true reflection of what I think good education should look and feel like.

The summer learning program my district is implementing is based on an outdoor education model. I could not possibly be more excited. After years, especially this last one, focused on making significant academic progress with students – of “catching up” all.the.time – of a focus on completion and percentages and compliance, this summer is all about fascination and discovery. It’s not that we don’t want the students to learn this summer, obviously, it’s that we want them to love to learn. The whole design reminds me of my childhood.

I spent years as a child, playing in the woods behind my house. With little more than my imagination (maybe a shovel, maybe some rope), I would spend hours walking trails, making forts, exploring the creek, getting dirty and getting involved in nature. I also spent hours curled up on a couch or in my room reading books. I spent hours writing stories, songs, poems, plays – anything that I could dream up, I would write down. I spent time with friends and while I thought we were just playing together, I was learning how to compromise, how to empathize and how to work together towards a goal. My family went camping and we spent time playing Yahtzee during rainstorms and Uno around a campfire. We ate simple meals that we all helped prepare and we spent hours traveling in a car without video games or movies to keep us entertained. In short, my childhood was spent experiencing the world around me. While my parents might have thought a camper meant “cheaper vacations for a family of five,” it gave me the opportunity to see new sights, new people, new activities, new adventures. I learned so much from these experiences.

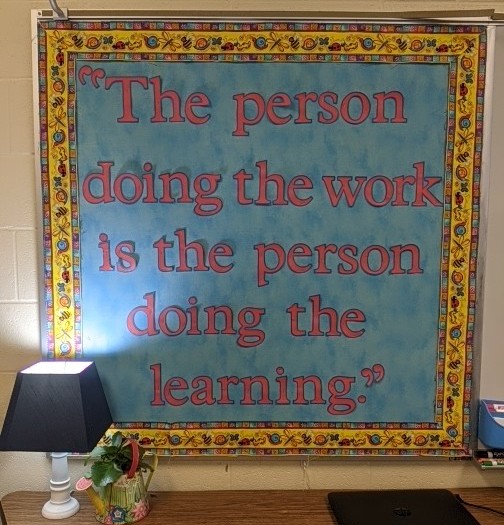

As adults, I remember my sister and I reflecting on something one of our children did, that he or she “just had to learn it the hard way”, implying that our kids couldn’t just take our word for something, they had to actually make the mistakes on their own to actually understand what we had been saying all along. We said this disparagingly. We said it as though our own children were less than smart for not modifying their own behavior based upon something wise we once shared with them. How foolish of us as parents! Children need to learn by doing. And doing means making mistakes. Often. To quote Ms. Frizzle of The Magic School Bus fame, “Get dirty! Take chances! Make mistakes!” Allowing students to experience life and then to mold learning around that experience is truly what lifelong learning is all about. And to experience life, you must get out there and be a part of the world.

I want my classroom to feel like my childhood. To feel open to possibilities and exploration. To feel available to all students every day no matter what mood they arrived in or what activities will come their way throughout the day. I want kids to feel like learning should be fun, but that it takes personal involvement. It isn’t a spectator sport from the second seat in the third row. Giving my students a choice of where to sit not only allows them the freedom to choose what is most comfortable – a chair, a twisty bucket seat, a couch, a pillow to lean on – it also gives them the opportunity to learn self-control, focus, attention and how to limit distractions. It teaches compromise, compassion and the joy of sharing. Just as I prefer to read and write in a comfortable, warm, cozy spot, I want my students to have the flexibility to learn from a place that is the most comfortable while being the most involved and productive as well.

These fifteen kids might not be lying awake in eager anticipation of summer school this morning as I am, but I hope that tomorrow or next week they are so eager to come experience learning that they are up early and bubbling with enthusiasm. And I hope that when they return full-time to school in the fall, that they will be just as eager, just as enthusiastic, just as involved in their learning. This is what learning should look and feel like. Childhood should be about exploring our world and learning how to navigate ourselves appropriately within it, in school and outside of it. It should be full of opportunities to try something new, to fail more often than succeed, but to also experience the joy of accomplishment that comes from hard work. I can’t wait to experience it with them.